Review and excerpts of the book Writing Science

Photo by Mike Tennion on Unsplash

Photo by Mike Tennion on UnsplashThis summer, my division had a fun workshop about storytelling. After that, a colleague recommended this book, Writing Science. Its core idea is that successful science writing tells a story. As a PhD student with English as a second language, I learned the importance of good writing for publishing. But it never occurred to me that being a scientist is, at the same time, being a writer. With a little suspicion to start with, the book truly opened my eyes after reading it.

The essential of this book is summarised by the below quote from the book introduction at Goodreads.

Writing Science is built upon the idea that successful science writing tells a story. It uses that insight to discuss how to write more effectively. Integrating lessons from other genres of writing with those from the author’s years of experience as author, reviewer, and editor, the book shows scientists and students how to present their research in a way that is clear and that will maximize reader comprehension.

Writing Science is cleanly structured, from the general ideas of good stories to typical structures corresponding to science writing (papers and proposals), and a top-down guide of how to write and rewrite individual sections, paragraphs, sentences, flow, and even words. The book teaches how to turn scientific papers into page-turners by setting an example itself. Moreover, it has detailed examples of good and bad writing and how to revise the bad ones. I made excerpts and notes while reading, and will definitely return to them frequently when writing future papers.

1. Principles to make an idea sticky (SUCCES)

Originally from Made to Stick by C. Heath and D. Heath (2007).

Simple. Use the ideas that the readers are familiar with to build an incrementally elaborate story.

Unexpected. Create good research questions with clearly defined knowledge gaps.

Concrete. Science is essentially creating abstraction of the complex reality. The dangerous zone is in the middle of the abstraction ladder from concrete data to universal laws taken for granted, where the abstract ideas and the path to reach them are less known.

By linking a concept to a concrete example, the concept itself becomes concrete—a new schema you can work with.

Credible. This goes hand in hand with being concrete. The opposite of credibility is buzzwords and hype without details and critical thinking.

Emotional. Ask engaging questions instead of accumulating trivia. It is life-or-death important for proposal writing.

Stories. This refers to the stories within a sticky story; not only the overall structure is important, but also the arcs within the big arc.

2. Story structure

| Story structure | Reader patience | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OCAR | Opening/Challenge/Action/Resolution | Slowest-take your time working into the story | Specialists' journals |

| ABDCE | Action/Background/Development/Climax/Ending | Faster-get right into the action | Proposals |

| LDR | Lead/Development/Resolution | Faster yet-but people will read to the end | Generalists' journals |

| LD | Lead/Development | Fastest-the whole story is up front | Newspaper articles |

2.1 Mapping OCAR into IMRaD (Introduction/Methods/Results and Discussion)

A scientific paper has a hourglass structure which starts wide with the opening (Introduction), narrows with the challenge and action (Methods/Results/Discussion), and widens back out again at the resolution (Conclusions).

Introduction

Opening. It shows the problem driving the research, the characters, and it targets an audience. Matching it to the resolution so that the readers will not feel cheated from overpromising or lose interest from underpromising.

Opening → Challenge. Don’t do data dump, but actively synthesize the information and narrow it down to the challenge.

Challenge: to learn X, we did Y. Questions vs. hypotheses is a matter of style and field, but not questions vs. objectives:

Focusing on objectives instead of questions is weak science and weak storytelling.

A good challenge is formed in an intellectual sequence instead of chronological one; it defines not only the data one collects but the knowledge one hopes to gain.

Methods, Results and Discussion

- Action: describe what you did (Methods) and what came of it (Results and Discussion).

- Methods. Describe it using LD structure with an initial overview for all and then the details for those who need them. This will make it easier for both novices and experts.

- Results and Discussion. It is a matter of style whether to separate them. However, readers need to distinguish what you found (Results) from what you think (Discussion). Data→Inference→Interpretation need clear boundaries between them, either by physical separation or using words like demonstrates and indicates (to identify inferences).

- Discussion. It needs its internal story structure. OCAR/LDR.

- Content: what to present. Choose the results that only contribute to the story. This is NOT cherry-picking the results. Every piece of information presented should not distract or confuse the readers.

Conclusions (Resolution)

Don’t blow the punchline.

- Weak. Being obvious and unconvincing. A typical way of writing a weak conclusion is to say X may provide insights into Y, but how? Be concrete and informative.

- Distracting. Don’t add “irrelevant” common sense or new information.

- Undermining conclusions. Don’t end with “more research is needed”, but use a concrete question opening up space for future study.

End proposals by reiterating problem, challenge, research, and how it will solve the problem.

3. Internal structure

A story arc consists of opening, development, and resolution, while each of sentences, paragraphs, or sections is a story arc. A paper itself is a set of nested arcs. At the top level, ask the below questions to check how well different components are organised.

1 Does each unit make a single, clear point? 2 When several paragraphs together form a section, are the linkages among them clear? 3 Has every extraneous thought that breaks the serial arc structure been removed? 4 When you introduce a topic, do you resolve that discussion before introducing a new topic? 5 Is every major unit of the work defined by either a subhead or clear opening text?

3.1 Paragraphs

The unit of composition.

| Point-first | Point-last |

|---|---|

| TS-D (Top sentence-development) | OCAR (Opening/Challenge/Action/Resolution) |

| LD (Lead/Development) | CDR (Lead/Development/Resolution) |

3.2 Sentences

A sentence tells a story, just the shortest one possible.

O - Opening - Subject (Topic)

C/A - Challenge/action - Verb

R - Resolution - Object (Stress)

- Putting topic and stress together

The words in a sentence have varying weights: stress, topic, and middle part in descending order of power. Put the right information in the right place.

- Subject-verb connection

The longer the gap between actor and action, the duller and more confusing a sentence becomes.

- Principles for more complex sentences

Even though we learn toward short sentences in science writing, it’s a useful skill to be able to craft a clean long one.

Pick the right topic. “It has been predicted that XX…” vs. “XX has been predicted to …”

Unburying the stress. “XX … was observed.” vs. “we observed XX…”

Guidelines

- Short and clear topic

- The main verb follows the topic immediately

- The key message comes at the stress

3.3 Flow

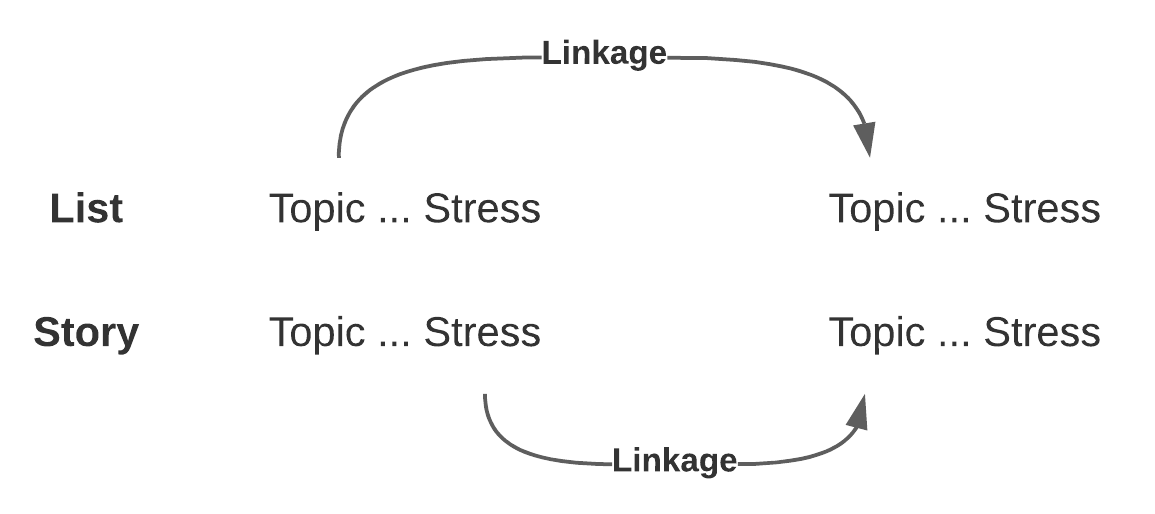

This is the crucial aspect contributing to a page turner. For the first time, I learned the difference between a list of sentences and a story. The difference is shown in the below figure adapted from Figure 13.2 of the book.

If done quickly, the first draft is usually full of scattered ideas and the thinking does not necessarily become a coherent story. When rewriting, one should turn lists of sentences into stories by putting the topic and the stress in the right place. Below are from Examples 13.1 and 13.2 of the book.

List. Molecules are comprised of covalently bonded atoms. Molecules' reactions are controlled by the strength of the bonds. Molecules, however, sometimes react slower than bond strength would predict.

Story. Molecules are comprised of covalently bonded atoms. Bond strength controls a molecule’s reactions. Sometimes however, those reactions are slower than bond strength would predict.

3.4 Energizing writing

- Active vs. passive voice. This controls whose story this is about. Passive voice sometimes is better when one needs to hide the actor and highlight the message.

- Fuzzy verbs. occur, facilitate, conduct, implement, affect, perform. Strong action verbs include modify, increase, react, accelerate, accomplish, decrease, inhibit, migrate, create, invade, disrupt.

- Nominalizations - the conversion of a word or phrase into a noun. This is the hardest part to avoid/revise. “Failure of … is observed” vs. “XX fail to …”

3.5 Words

Jargon. A term that refers to a schema the reader does not hold and for which there is an adequate plain language equivalent.

Technical terms. A term that refers to a schema the reader does hold and for which either there is no plain language equivalent or where using it would be confusing.

- Beginning of the sentence. Every reader knows and understands the term.

- End of the sentence. Define a new term for the reader.

- Middle of the sentence. Most readers know the term while it is not critical to the story.

Avoid being unnecessarily technical where there is plain language equivalent.

Emotional weight.

Despite the benefits of short, light words, academics routinely fall into the centuries-old trap of choosing long, heavy Latin words. Many of us are still showing off instead of communicating.

Consume vs Eat, Permit vs. Let, Initiate vs. Start, Utilize vs. Use, Attempt vs. Try…

Prepositional phrases vs. compound nouns. “rate of reaction vs. reaction rate”.

4 Real editing

4.1 Condensing

Strategies for condensing. 1) Redundancies, 2) Obvious, 3) Modifiers: adjectives and adverbs, 4) Metadiscourse, and 5) Verbosity.

- Metadiscourse. “We found that …”, “We argue that …”, “These results may indicate …”.

I used metadiscourse a lot because of lacking the sense to take care of the flow; I was driven by the data and doing data dump instead of synthesize the results into a story. These metadiscourses disrupt the flow easily and should be consciously avoided.

- Putting it all together. 1) Structure, 2) Clarity, 3) Flow, and 4) Language.

4.2 Dealing with limitations

- Introduction. Promise the story you will deliver.

- Materials and methods. Acknowledge it sooner than later especially the method is not standard.

- Discussion. Use “but, yes” to remind of the limitations but don’t dwell on them.

- Within the conclusions. Never end with the specific limitations but open up the future research with concrete questions.

The above notes omit the last three chapters, “Writing global science”, “Writing for the public”, and “Resolution”, and the appendices of writing resources.

After reading this book, I started writing a new paper. The related work part took me two weeks to finish. I write in a completely different way with all the knowledge learned from this book. I became more cautious and therefore, painfully slower in writing down anything. But I guess it is a process, trust it and you will become a better writer. Have fun writing science!